Marble Inscribed Cippus in the Metropolitan Museum…

Marble Inscribed Cippus in the Metropolitan Museum…

Julio-Claudian Funerary Altar in the Metropolitan…

Julio-Claudian Funerary Altar in the Metropolitan…

Detail of a Julio-Claudian Funerary Altar in the M…

Square with a Bucolic Landscape in the Metropolita…

Tapestry Fragment with Two Figures in the Metropol…

Glass Cage Cup Vivas Diatretum in the Metropolitan…

Glass Cage Cup Vivas Diatretum in the Metropolitan…

Pentelic Marble Fragment of a Hero Relief in the M…

Pentelic Marble Fragment of a Hero Relief in the M…

Bronze Statues of Girls Chasing Partridges in the…

Bronze Statues of Girls Chasing Partridges in the…

Bronze Statues of Girls Chasing Partridges in the…

Bronze Statues of Girls Chasing Partridges in the…

Bronze Statues of Girls Chasing Partridges in the…

Bronze Statues of Girls Chasing Partridges in the…

Bronze Statues of Girls Chasing Partridges in the…

Bronze Statues of Girls Chasing Partridges in the…

Bronze Statues of Girls Chasing Partridges in the…

Bronze Statues of Girls Chasing Partridges in the…

Bronze Statues of Girls Chasing Partridges in the…

Bronze Statues of Girls Chasing Partridges in the…

Human-Headed Winged Genie Relief in the Metropolit…

Detail of the Veranda Post with an Equestrian Figu…

Detail of the Veranda Post with an Equestrian Figu…

Veranda Post with an Equestrian Figure and Female…

Veranda Post with an Equestrian Figure and Female…

Latin Bible with Leather Binding in the Metropolit…

Detail of a Jester Candle-holder in the Metropolit…

Jester Candle-holder in the Metropolitan Museum of…

Reliquary Monstrance of St. John the Baptist in th…

Reliquary Monstrance of St. John the Baptist in th…

Fayum Portrait of a Young Woman in Red in the Metr…

Fayum Portrait of a Young Woman in Red in the Metr…

Falcata Type Sword in the Metropolitan Museum of A…

Falcata Type Sword in the Metropolitan Museum of A…

Detail of the Fresco of the Banquet Scene from the…

Detail of the Fresco of the Banquet Scene from the…

Detail of the Fresco of the Banquet Scene from the…

Detail of the Fresco of the Banquet Scene from the…

Detail of the Fresco of the Banquet Scene from the…

Detail of the Fresco of the Banquet Scene from the…

Detail of the Fresco of the Banquet Scene from the…

Detail of the Fresco of the Banquet Scene from the…

See also...

Keywords

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

118 visits

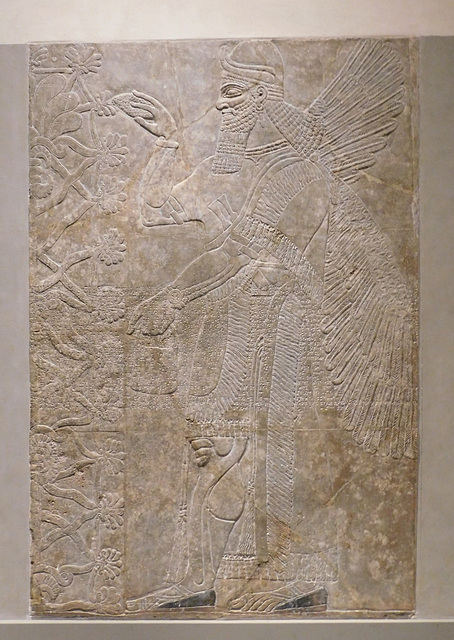

Human-Headed Winged Genie Relief in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, August 2019

Title: Relief panel

Period: Neo-Assyrian

Date: ca. 883–859 BCE

Geography: Mesopotamia, Nimrud (ancient Kalhu)

Culture: Assyrian

Medium: Gypsum alabaster

Dimensions: 92 1/2 x 61 1/2 x 2 1/8 in. (235 x 156.2 x 5.4 cm)

Credit Line: Gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr., 1931

Accession Number: 31.72.1

This panel from the Northwest Palace at Nimrud (ancient Kalhu) depicts a winged supernatural figure. Such figures appear throughout the palace, sometimes flanking either the figure of the Assyrian king or a stylized "sacred tree." The reliefs were painted, but today almost none of the original pigment survives. This panel is a rare exception, with some paint clearly visible on the figure’s sandals. Where pigment has survived on reliefs, it has often been near the bases. One suggested explanation for this has been that after the fall of the Assyrian empire and the sacking of its palaces at the end of the seventh century B.C., these areas were immediately buried in debris, and thus afforded more protection from weathering than the rest of the reliefs.

The figure depicted on the panel is human-headed and faces left, holding in his left hand a bucket and in his right hand a cone whose exact nature is unclear. One suggestion has been that the gesture, sometimes performed as here by figures flanking a sacred tree, is symbolic of fertilization: the "cone" resembles the male date spathe used by Mesopotamian farmers, with water, to artificially fertilize female date-palm trees. It does seem likely that the cone was supposed to hold and dispense water from the bucket in this way, but it is described in Akkadian as a "purifier," and the fact that figures performing this gesture are also shown flanking the king suggests that some purifying or protective meaning is present. The figure wears a horned cap, indicating divinity, and jewelry: visible are a large pendant earring, a collar consisting of two bands of beads and spacers, a further collar with pendant tassel, armlets, and bracelets, on one of which can be seen a large central rosette symbol associated with divinity and perhaps particularly with the goddess Ishtar. Although we cannot know how these elements were originally painted, excavated parallels include elaborate jewelry in gold, inlaid with semi-precious stones. A collar or necklace such as that shown here might have been made up of semi-precious stones separated by gold spacer beads. The figure carries two knives, tucked into a belt with their handles visible at chest level.

The tree represents no real plant, and the form in which it is depicted varies within Neo-Assyrian art. The tree is generally thought to be a symbol of the agricultural fertility and abundance, and probably the more general prosperity, of Assyria. If this is so, then in protecting the tree and the king the winged figures of the Northwest Palace are all engaged in the protection of the Assyrian state.

The figures are supernatural but do not represent any of the great gods. Rather, they are part of the vast supernatural population that for ancient Mesopotamians animated every aspect of the world. They appear as either eagle-headed or human-headed and wear a horned crown to indicate divinity. Both types of figure usually have wings. Because of their resemblance to groups of figurines buried under doorways for protection whose identities are known through ritual texts, it has been suggested that the figures in the palace reliefs represent the apkallu, wise sages from the distant past. This may indeed be one level of their symbolism, but protective figures of this kind are likely to have held multiple meanings and mythological connections.

Figures such as these continued to be depicted in later Assyrian palaces, though less frequently. Only in the Northwest Palace do they form such a dominant feature of the relief program. Also unique to the Northwest Palace is the so-called Standard Inscription that ran across the middle of every relief, often cutting across the imagery. The inscription, carved in cuneiform script and written in the Assyrian dialect of the Akkadian language, lists the achievements of Ashurnasirpal II (r. 883–859 B.C.), the builder of the palace. After giving his ancestry and royal titles, the Standard Inscription describes Ashurnasirpal’s successful military campaigns to east and west and his building works at Nimrud, most importantly the construction of the palace itself. The inscription is thought to have had a magical function, contributing to the divine protection of the king and the palace.

Text from: www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/322593

Period: Neo-Assyrian

Date: ca. 883–859 BCE

Geography: Mesopotamia, Nimrud (ancient Kalhu)

Culture: Assyrian

Medium: Gypsum alabaster

Dimensions: 92 1/2 x 61 1/2 x 2 1/8 in. (235 x 156.2 x 5.4 cm)

Credit Line: Gift of John D. Rockefeller Jr., 1931

Accession Number: 31.72.1

This panel from the Northwest Palace at Nimrud (ancient Kalhu) depicts a winged supernatural figure. Such figures appear throughout the palace, sometimes flanking either the figure of the Assyrian king or a stylized "sacred tree." The reliefs were painted, but today almost none of the original pigment survives. This panel is a rare exception, with some paint clearly visible on the figure’s sandals. Where pigment has survived on reliefs, it has often been near the bases. One suggested explanation for this has been that after the fall of the Assyrian empire and the sacking of its palaces at the end of the seventh century B.C., these areas were immediately buried in debris, and thus afforded more protection from weathering than the rest of the reliefs.

The figure depicted on the panel is human-headed and faces left, holding in his left hand a bucket and in his right hand a cone whose exact nature is unclear. One suggestion has been that the gesture, sometimes performed as here by figures flanking a sacred tree, is symbolic of fertilization: the "cone" resembles the male date spathe used by Mesopotamian farmers, with water, to artificially fertilize female date-palm trees. It does seem likely that the cone was supposed to hold and dispense water from the bucket in this way, but it is described in Akkadian as a "purifier," and the fact that figures performing this gesture are also shown flanking the king suggests that some purifying or protective meaning is present. The figure wears a horned cap, indicating divinity, and jewelry: visible are a large pendant earring, a collar consisting of two bands of beads and spacers, a further collar with pendant tassel, armlets, and bracelets, on one of which can be seen a large central rosette symbol associated with divinity and perhaps particularly with the goddess Ishtar. Although we cannot know how these elements were originally painted, excavated parallels include elaborate jewelry in gold, inlaid with semi-precious stones. A collar or necklace such as that shown here might have been made up of semi-precious stones separated by gold spacer beads. The figure carries two knives, tucked into a belt with their handles visible at chest level.

The tree represents no real plant, and the form in which it is depicted varies within Neo-Assyrian art. The tree is generally thought to be a symbol of the agricultural fertility and abundance, and probably the more general prosperity, of Assyria. If this is so, then in protecting the tree and the king the winged figures of the Northwest Palace are all engaged in the protection of the Assyrian state.

The figures are supernatural but do not represent any of the great gods. Rather, they are part of the vast supernatural population that for ancient Mesopotamians animated every aspect of the world. They appear as either eagle-headed or human-headed and wear a horned crown to indicate divinity. Both types of figure usually have wings. Because of their resemblance to groups of figurines buried under doorways for protection whose identities are known through ritual texts, it has been suggested that the figures in the palace reliefs represent the apkallu, wise sages from the distant past. This may indeed be one level of their symbolism, but protective figures of this kind are likely to have held multiple meanings and mythological connections.

Figures such as these continued to be depicted in later Assyrian palaces, though less frequently. Only in the Northwest Palace do they form such a dominant feature of the relief program. Also unique to the Northwest Palace is the so-called Standard Inscription that ran across the middle of every relief, often cutting across the imagery. The inscription, carved in cuneiform script and written in the Assyrian dialect of the Akkadian language, lists the achievements of Ashurnasirpal II (r. 883–859 B.C.), the builder of the palace. After giving his ancestry and royal titles, the Standard Inscription describes Ashurnasirpal’s successful military campaigns to east and west and his building works at Nimrud, most importantly the construction of the palace itself. The inscription is thought to have had a magical function, contributing to the divine protection of the king and the palace.

Text from: www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/322593

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2025

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter

Sign-in to write a comment.