Letter from a Freed Man: Jourdan Anderson

Siah Hulett Carter: Escape on the Monitor

Ruth Cox Adams

Ellen Craft

No Longer Hidden

The Woman Who Escaped Enslavement by President Geo…

George W Lowther

Edmondson Sisters

The Truth's Daughter

Please Hear Our Prayers

Caldonia Fackler 'Cal' Johnson

Nancy Green

The Gardners

3X Great Grandson Remembers

Frederick Foote, Sr.

Samuel Harper and Jane Hamilton

Wiley Hinds

John H Nichols

Nelson Gant

Ann Bicknell Ellis

The Story of James Henry Brooks

Hero of Richmond Theater Disaster

Howard Henriques Smith

George O. Brown

Sara Baro Colcher

Freedom with the Joneses

Jim Hercules

The Inalienable Right to be Free

Henry Bibb

Captured Faces

Sylvia Conner

Mary Jane Conner

The Freeman Girls

Christiana Taylor Livingston Williams Freeman

A Hazardous Life: The Story of Nahum Gardner Hazar…

Hugh M Burkett

Dr. Henry Morgan Green

William Still

G. Grant Williams

Robert J Wilkinson

Michael Francis Blake

Lafayette Alonzo Tillman

Mr. Hendricks

Lorenzo Dow Turner

Robert H McNeill

See also...

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

7 visits

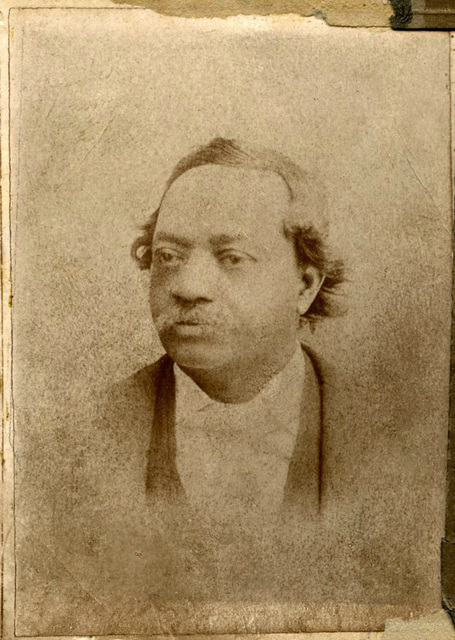

John Dabney

John Dabney's mother was a cook, his father a carriage driver, in Hanover Junction. Dabney started in service work as a jockey, burnishing the reputations of the DeJarnettes, the white family that held his own family in bondage. When he outgrew the saddle, he headed inside the region’s racecourse buildings to prepare and serve food. There, Dabney began acquiring the skills that would attach to his biography terms that we rarely associate with those who were enslaved: bartender, chef, caterer. These were the stations from which, as a Richmond paper wrote upon his death, he supervised the city’s "every gathering of importance."

Cora Williamson DeJarnette inherited Dabney's mother through her marriage to William DeJarnette, who died not long after their wedding. Cora, presumably confronting limited resources as a young widow and in need of income, allowed her brother, Dabney Williamson, to hire-out Dabney to a restaurant at the railroad station in Gordonsville, Virginia. She would earn his wages while he garnered skills to make him, as newspapers later attested, "a very valuable servant." In Gordonsville, Dabney's son Wendell later wrote, the young man displayed a knack for the work. He reached the position of head waiter at the age of 18.

By the late 1850s, Dabney moved from the Columbian Hotel to run the kitchen and bar at the Ballard House & Exchange Hotel — the establishment, as his son Wendell later wrote, recognized by many as "the leading hotel in Virginia's leading city." Dabney took the helm after the departure of Spiro Zetelle, a well-regarded cook of Greek origin who excelled in restaurants and catering in Richmond until moving to California in the 1880s. Dabney inherited Zetelle's menu, a complex lineup of 19th-century fine dining standards, and the praise of his patrons indicates that he mastered it.

Between his arrival in Richmond and the beginning of the Civil War, John Dabney married Elizabeth Foster, another enslaved black Virginian. The couple soon welcomed a son, Clarence. But the birth was not celebrated by all in their orbit. John and Elizabeth Dabney's younger son, Wendell, later wrote that Elizabeth's owners thought she was focusing too much on her newborn child and not enough on their own family. "Dissatisfaction at this," Wendell wrote, "and rapidly growing debts, caused them to decide upon selling her."

Faced with the horror of losing his wife and son, likely forever — neither state nor federal law recognized enslaved people as members of families, and offered no protection nor support for reunification — Dabney turned to his savings. His work at hotels and restaurants principally benefitted Cora DeJarnette, but Dabney, as with fellow enslaved Virginians hired-out from farms around Richmond to factory and hospitality trades in the capital, was able to save tips. Dabney had made an agreement with DeJarnette to buy his own freedom through those tips. But his resources, while exceptional for an enslaved person, could stretch only so far. He asked permission to pause his payments in order to secure the funds necessary to free his wife. Cora DeJarnette agreed. "Then," Wendell explained, after enlisting "the help of some of his white friends" to arrange documents for the purchase, Dabney gathered the funds, "and bought my mother."

War, slowly and with great doubt, eventually brought freedom. The United States Army, including a regiment of U.S. Colored Troops, liberated Richmond on April 3, 1865. Fires set by retreating Confederates had destroyed the city's industrial district and commercial core, including the Columbian Hotel, where John Dabney first drew public acclaim. Elizabeth Dabney labored to sustain her business of washing, pressing, and repairing clothes. Her husband sought new opportunities. Richmond residents, black and white, began to rebuild, and the burned district provided some of the most promising sites for new development.

One such site was an 11-room women's seminary converted into a home and sold at auction in 1866. Two blocks from the State Capitol, the home at 1414 East Broad Street, on the city's main corridor, caught Dabney's eye as he walked by one day in November. John Dabney later told Wendell that he stood watching a large crowd of onlookers — and few bidders — while unintentionally nodding as the auctioneer announced sums climbing higher and higher. Bidders grew silent, Wendell later wrote, and finally the verdict was in: "Going, going, gone! Knocked down to John Dabney." The promising businessman and young father could just barely afford the final price. His accidental purchase, which became the family's home for more than 30 years, required a loan. But credit wasn't a stretch for John Dabney.

Wendell's autobiographical sketch relays the family lore that became Richmond legend. After the war, Cora DeJarnette became "destitute." She no longer enjoyed the income Dabney's work had supplied, nor the regular payments he made to acquire his freedom. Dabney had resumed making those payments after freeing Elizabeth. But eventually, the depreciation of Confederate currency caused DeJarnette to call for a pause — and with Emancipation, this last source of income seemed to have vanished.

Dabney learned of DeJarnette's plight and paid her a visit. He offered to pay her the balance that remained on his debt when Richmond was freed. Wendell Dabney wrote that his father felt indebted to DeJarnette due to her willingness to let him suspend payments when he faced the prospect of losing his wife. John Dabney told his son that Cora DeJarnette protested, but he did not waver. "I am keeping my word," he reported telling her. John Dabney placed before her a stack of United States currency, and then walked out.

"Richmond," Wendell wrote, "never forgot the deed. My father's note was good at any bank, and his word equivalent to an oath."

The city's white newspapers applauded Dabney's dignity. "All of our people are familiar with John Dabney, the celebrated colored restaurateur of our city," the breathless first account read, "and those who know him best place the most implicit confidence in his honor, and a circumstance which came to our knowledge a few days since proves how worthily this confidence is bestowed." In one remarkable act, Dabney transformed his reputation. He grew his wide acclaim into instant legend.

The story hit the press in September 1866. It circulated throughout Virginia and elsewhere in the South, and appeared in a Richmond newspaper as late as 1938. Over those 72 years, the paternalistic tone of the accounts softened, but remained. White Richmond interpreted Dabney's action as the simple gratefulness of a simple man. They praised DeJarnette's generosity in permitting Dabney to pause payments for his own freedom without acknowledging what she stood to gain from the long-term arrangement, nor, most fundamentally, the fact that she held him in bondage until the war made it impossible. The papers emphasized Dabney's "sense of honesty and personal obligation" without considering that an observer of white elites in the recent capital of the Confederacy might have eyed the tenuous future and sought to cement his place in any way possible. "John will stand," read the first report, "higher than ever in the estimation of every Richmond gentleman." And so he did, whatever his own feelings.

Dabney could not print an expansion of this narrative; slavery had made it impossible for him to learn to read or write. Wendell notes that on the one occasion when a family member of his owner's tried to teach him, "she was detected and sent away, while he received a severe whipping." But John and Elizabeth Dabney left no doubt about their politics. When Elizabeth gave birth to their son, Wendell Phillips, in November 1865, seven months after Emancipation reached Richmond, the couple named him after an abolitionist.

John Dabney told his son Wendell that his "business was too durn good" to leave town and make a new start elsewhere. But in staying, John and Elizabeth Dabney resisted by building a legacy. They sent Wendell to Oberlin College, where he studied music. Wendell returned to Richmond for several years, a young graduate finding his way, teaching grade school, and writing music, before returning to Ohio. In Cincinnati, he founded an opera company, two newspapers, and the local chapter of the NAACP; served twenty-seven years as the city's paymaster, Cincinnati's first black citizen to hold the post; and became a lifelong advocate for African American civil rights.

The other Dabney children, most born in the wake of freedom, also charted impressive paths. Daughters Kate and Hattie became teachers. John Milton, perhaps channeling the epic imagination of his namesake, excelled in professional baseball and later through a 30-year career in the U.S. Postal Service. Eldest son Clarence, whom John Dabney had rescued from sale in the late-1850s, followed his father into the hospitality trade.

Dabney may have retired from managing his restaurant and catering business early in the 1890s, but he continued to work until the week of his death. He died at his Richmond home on June 7, 1900. All four of the city's daily newspapers reported his death, but none indicated in which of Richmond's African American cemeteries he was buried.

This narrative of John Dabney's life written by the film's (The Hail-Storm: John Dabney in Virginia) co-directors, Hannah Ayers and Lance Warren, draws together existing scholarship and presents previously unpublished sources and facts discovered during research for the film in Summer and Fall 2017; Virginia Humanities; Author Maureen Egan discovered the long hidden photograph of Dabney, the only known photograph of him, in 2015 at The Valentine, the preeminent museum of the history of Richmond, Virginia.

Cora Williamson DeJarnette inherited Dabney's mother through her marriage to William DeJarnette, who died not long after their wedding. Cora, presumably confronting limited resources as a young widow and in need of income, allowed her brother, Dabney Williamson, to hire-out Dabney to a restaurant at the railroad station in Gordonsville, Virginia. She would earn his wages while he garnered skills to make him, as newspapers later attested, "a very valuable servant." In Gordonsville, Dabney's son Wendell later wrote, the young man displayed a knack for the work. He reached the position of head waiter at the age of 18.

By the late 1850s, Dabney moved from the Columbian Hotel to run the kitchen and bar at the Ballard House & Exchange Hotel — the establishment, as his son Wendell later wrote, recognized by many as "the leading hotel in Virginia's leading city." Dabney took the helm after the departure of Spiro Zetelle, a well-regarded cook of Greek origin who excelled in restaurants and catering in Richmond until moving to California in the 1880s. Dabney inherited Zetelle's menu, a complex lineup of 19th-century fine dining standards, and the praise of his patrons indicates that he mastered it.

Between his arrival in Richmond and the beginning of the Civil War, John Dabney married Elizabeth Foster, another enslaved black Virginian. The couple soon welcomed a son, Clarence. But the birth was not celebrated by all in their orbit. John and Elizabeth Dabney's younger son, Wendell, later wrote that Elizabeth's owners thought she was focusing too much on her newborn child and not enough on their own family. "Dissatisfaction at this," Wendell wrote, "and rapidly growing debts, caused them to decide upon selling her."

Faced with the horror of losing his wife and son, likely forever — neither state nor federal law recognized enslaved people as members of families, and offered no protection nor support for reunification — Dabney turned to his savings. His work at hotels and restaurants principally benefitted Cora DeJarnette, but Dabney, as with fellow enslaved Virginians hired-out from farms around Richmond to factory and hospitality trades in the capital, was able to save tips. Dabney had made an agreement with DeJarnette to buy his own freedom through those tips. But his resources, while exceptional for an enslaved person, could stretch only so far. He asked permission to pause his payments in order to secure the funds necessary to free his wife. Cora DeJarnette agreed. "Then," Wendell explained, after enlisting "the help of some of his white friends" to arrange documents for the purchase, Dabney gathered the funds, "and bought my mother."

War, slowly and with great doubt, eventually brought freedom. The United States Army, including a regiment of U.S. Colored Troops, liberated Richmond on April 3, 1865. Fires set by retreating Confederates had destroyed the city's industrial district and commercial core, including the Columbian Hotel, where John Dabney first drew public acclaim. Elizabeth Dabney labored to sustain her business of washing, pressing, and repairing clothes. Her husband sought new opportunities. Richmond residents, black and white, began to rebuild, and the burned district provided some of the most promising sites for new development.

One such site was an 11-room women's seminary converted into a home and sold at auction in 1866. Two blocks from the State Capitol, the home at 1414 East Broad Street, on the city's main corridor, caught Dabney's eye as he walked by one day in November. John Dabney later told Wendell that he stood watching a large crowd of onlookers — and few bidders — while unintentionally nodding as the auctioneer announced sums climbing higher and higher. Bidders grew silent, Wendell later wrote, and finally the verdict was in: "Going, going, gone! Knocked down to John Dabney." The promising businessman and young father could just barely afford the final price. His accidental purchase, which became the family's home for more than 30 years, required a loan. But credit wasn't a stretch for John Dabney.

Wendell's autobiographical sketch relays the family lore that became Richmond legend. After the war, Cora DeJarnette became "destitute." She no longer enjoyed the income Dabney's work had supplied, nor the regular payments he made to acquire his freedom. Dabney had resumed making those payments after freeing Elizabeth. But eventually, the depreciation of Confederate currency caused DeJarnette to call for a pause — and with Emancipation, this last source of income seemed to have vanished.

Dabney learned of DeJarnette's plight and paid her a visit. He offered to pay her the balance that remained on his debt when Richmond was freed. Wendell Dabney wrote that his father felt indebted to DeJarnette due to her willingness to let him suspend payments when he faced the prospect of losing his wife. John Dabney told his son that Cora DeJarnette protested, but he did not waver. "I am keeping my word," he reported telling her. John Dabney placed before her a stack of United States currency, and then walked out.

"Richmond," Wendell wrote, "never forgot the deed. My father's note was good at any bank, and his word equivalent to an oath."

The city's white newspapers applauded Dabney's dignity. "All of our people are familiar with John Dabney, the celebrated colored restaurateur of our city," the breathless first account read, "and those who know him best place the most implicit confidence in his honor, and a circumstance which came to our knowledge a few days since proves how worthily this confidence is bestowed." In one remarkable act, Dabney transformed his reputation. He grew his wide acclaim into instant legend.

The story hit the press in September 1866. It circulated throughout Virginia and elsewhere in the South, and appeared in a Richmond newspaper as late as 1938. Over those 72 years, the paternalistic tone of the accounts softened, but remained. White Richmond interpreted Dabney's action as the simple gratefulness of a simple man. They praised DeJarnette's generosity in permitting Dabney to pause payments for his own freedom without acknowledging what she stood to gain from the long-term arrangement, nor, most fundamentally, the fact that she held him in bondage until the war made it impossible. The papers emphasized Dabney's "sense of honesty and personal obligation" without considering that an observer of white elites in the recent capital of the Confederacy might have eyed the tenuous future and sought to cement his place in any way possible. "John will stand," read the first report, "higher than ever in the estimation of every Richmond gentleman." And so he did, whatever his own feelings.

Dabney could not print an expansion of this narrative; slavery had made it impossible for him to learn to read or write. Wendell notes that on the one occasion when a family member of his owner's tried to teach him, "she was detected and sent away, while he received a severe whipping." But John and Elizabeth Dabney left no doubt about their politics. When Elizabeth gave birth to their son, Wendell Phillips, in November 1865, seven months after Emancipation reached Richmond, the couple named him after an abolitionist.

John Dabney told his son Wendell that his "business was too durn good" to leave town and make a new start elsewhere. But in staying, John and Elizabeth Dabney resisted by building a legacy. They sent Wendell to Oberlin College, where he studied music. Wendell returned to Richmond for several years, a young graduate finding his way, teaching grade school, and writing music, before returning to Ohio. In Cincinnati, he founded an opera company, two newspapers, and the local chapter of the NAACP; served twenty-seven years as the city's paymaster, Cincinnati's first black citizen to hold the post; and became a lifelong advocate for African American civil rights.

The other Dabney children, most born in the wake of freedom, also charted impressive paths. Daughters Kate and Hattie became teachers. John Milton, perhaps channeling the epic imagination of his namesake, excelled in professional baseball and later through a 30-year career in the U.S. Postal Service. Eldest son Clarence, whom John Dabney had rescued from sale in the late-1850s, followed his father into the hospitality trade.

Dabney may have retired from managing his restaurant and catering business early in the 1890s, but he continued to work until the week of his death. He died at his Richmond home on June 7, 1900. All four of the city's daily newspapers reported his death, but none indicated in which of Richmond's African American cemeteries he was buried.

This narrative of John Dabney's life written by the film's (The Hail-Storm: John Dabney in Virginia) co-directors, Hannah Ayers and Lance Warren, draws together existing scholarship and presents previously unpublished sources and facts discovered during research for the film in Summer and Fall 2017; Virginia Humanities; Author Maureen Egan discovered the long hidden photograph of Dabney, the only known photograph of him, in 2015 at The Valentine, the preeminent museum of the history of Richmond, Virginia.

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2024

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter