The Freeman Girls

Mary Jane Conner

Sylvia Conner

Captured Faces

Henry Bibb

The Inalienable Right to be Free

Jim Hercules

Freedom with the Joneses

Sara Baro Colcher

George O. Brown

John Dabney

Letter from a Freed Man: Jourdan Anderson

Siah Hulett Carter: Escape on the Monitor

Ruth Cox Adams

Ellen Craft

No Longer Hidden

The Woman Who Escaped Enslavement by President Geo…

George W Lowther

Edmondson Sisters

The Truth's Daughter

Please Hear Our Prayers

Caldonia Fackler 'Cal' Johnson

Nancy Green

A Hazardous Life: The Story of Nahum Gardner Hazar…

Hugh M Burkett

Dr. Henry Morgan Green

William Still

G. Grant Williams

Robert J Wilkinson

Michael Francis Blake

Lafayette Alonzo Tillman

Mr. Hendricks

Lorenzo Dow Turner

Robert H McNeill

Wendell Phillips Dabney

Orrin C Evans

Dr. William A 'Bud' Burns

Matthew Anderson

William Monroe Trotter

James E Reed

Henry Lee Price

Frederick Douglass

Samuel R. Lowery: First Black Lawyer to Argue a C…

Edward Elder Cooper

Columbus Ohio's First African American Aviator

See also...

Authorizations, license

-

Visible by: Everyone -

All rights reserved

-

12 visits

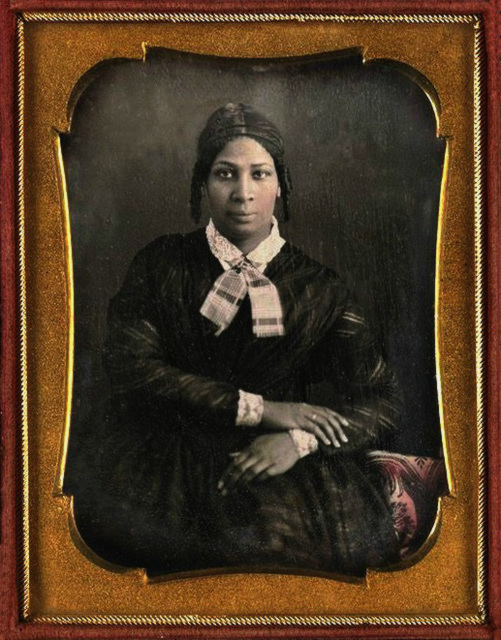

Christiana Taylor Livingston Williams Freeman

Slavery A Family Divided History: The Relationship Between Two People Long Dead Reaches Down Through Time to Shape the Lives of their Descendants, Black and White

The Baltimore Sun

Madeline Wheeler Murphy

Daguerreotype courtesy of Christopher Rabb

June 29, 1997

My childhood recollections of the Fourth of July are punctuated by picnics, parades and my father's claim that he was related to one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. My family paid little heed to Pop's claim, and he ** made very little of it. There was no hard proof, just an oral history handed down from his mother.

Although my hometown, Wilmington, Delaware, was segregated, Pop always told us that the Declaration of Independence was an important document. On one particular July Fourth, when I was about 10 years old, I remember him repeating these words in a voice heavy with irony:

"We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness."

No sooner had Pop finished than he uttered an anguished sigh and set off a rocket, which rose toward the heavens and exploded with vengeance. It was if Pop had said, "Take that, you lying s.o.b.'s."

As young as I was, I felt my father's anguish as a "colored girl" attending segregated schools, pools and tennis courts. I was not even allowed to sit in the white movie house balconies, nor at Woolworth's lunch counter for an ice cream soda, not even in the children's room of the public library. Equal, indeed!

After my father had died, the memory of his claim haunted me so much that I asked his sister, Mary Alice Wheeler McNeill, about it. Referring to my great-great-grandmother, she wrote: "Christina Williams was one daughter of a West Indian woman and Philip Livingstone [sic], a member of a prominent New York family."

My aunt wrote her letter in 1950. More than 40 years passed before the relationship between Philip Henry Livingston - the grandson of a signer of the Declaration of Independence - and his enslaved Jamaican, Barbara Williams, was authenticated.

Over the years, I had grown frustrated trying to track down the truth, but my grandson, Christopher Murphy Rabb, a Yale graduate who majored in African and African-American history, was intrigued by the story and confirmed it.

Trying to follow the Livingstons' family tree is very confusing because so many family members have the same or similar names. My aunt said they were "prominent" - which turned out to be an understatement.

By the time the American Revolution began, the Livingston family owned approximately 1 million acres on both sides of the Hudson River in upstate New York.

The empire began when the Crown gave Robert Livingston (1654-1728), the family patriarch, 160,000 acres. When the elder Livingston died, Robert Livingston Jr. (1688-1775) began building Clermont, the Georgian-style family home that is now a historic site.

Robert Livingston Jr.'s only child, Robert R. Livingston (1718-1775), married Margaret Beekman, the heir to some 250,000 acres of land that became part of the Livingstons' holdings. Robert R. Livingston served as judge of the Admiralty Court and judge of the Supreme Court of the Province of New York.

Robert R. Livingston Jr. (1746-1813) is probably the best-known member of the family. He was the eldest son of Robert, the judge, and Margaret Beekman. He also was a member of the Committee of Five that drafted the Declaration of Independence, and he became the first United States minister of foreign affairs (secretary of state). While serving as chancellor of the state of New York, he gave the oath of office to George Washington after he became the nation's first president. Although Robert R. Livingston Jr. helped draw up the Declaration of Independence, he didn't sign it. Philip Livingston, a first cousin once removed, actually signed the document.

In 1812, Philip Henry Livingston, the grandson of the signer of the Declaration of Independence, fathered a daughter by an enslaved woman, Barbara Williams. That daughter was Christiana Taylor Williams (1812 - 1903).

After a yearlong correspondence with a member of the Livingston family, my grandson Christopher found the 1909 Brooklyn, N.Y., copy of Christiana's death certificate. It listed Philip Livingston as her father and Barbara as her mother.

Last year, the descendants of Barbara and Christiana Williams were invited to the Livingston family reunion at the family mansion in Clermont, which is now a state preserve open to the public.

Christopher was invited to make a formal presentation. It was held under a tent that seated 75 to 100 family members, who had mixed reactions to his findings.

Some were curious and asked questions; others averted their eyes and retreated; a few scanned the genealogical charts quietly and spoke to Christopher almost in whispers, obviously embarrassed or uncomfortable with his presentation.

Despite some consternation on the part of a few Livingstons, the local newspaper - ironically called the Kingston Freedman carried a story about the reunion and the Livingstons' black descendants.

It ran with a headline that said: "Mr. and Mrs. Livingston, I presume - Annual reunion in Clermont includes black descendants."

After I arrived at Clermont, I realized that what had been a footnote in my aunt's letter and Pop's sketchy verbal history had come to fore. I rode to the reunion on a lark, but now I had a lump in my throat.

As I stood at the registration desk, putting on my name tag, I realized that I might have been standing where Barbara Williams, my great-great-great grandmother, stood two centuries ago. The registration table sat where some 150 enslaved had been quartered.

Now it was a grassy meadow. All vestiges of slavery with its secrets, graveyards and debauchery had been leveled and buried.

All the jocularity, the sardonic "guess who's coming to dinner" banter had vanished. I felt I was in the center of a whirlpool, enveloped by ghosts.

No government sanctioned apology could assuage the pain I felt for Barbara as a concubine on call whenever Philip lusted after her. Imagine how the other enslaved must have shunned her, taunted her and perhaps even physically attacked her becaused of her relationship with "Massah."

The impact of walking where Barbara had walked and seeing what she had seen took my breath away and churned the pit of my stomach. At the same time, I felt like running away from the ugly truth of my personal proximity to slavery.

Rushing by me, a woman with her child in tow smiled in a patronizing way and asked in the lilting voice mothers use with their children, "Are they treating you all right?"

Out of a daze I mumbled with disdain, "Why wouldn't they?" She became flustered, smiled again, shrugged her shoulders and resumed her walk.

The growing empathy for Barbara was still with me in spirit. Although the woman's question was innocuous, it made me feel like a child who was somehow inferior. I realized that Barbara must have felt the same way much of the time.

I also realized that the woman could not have understood how I felt. Our lives are parallel lines that will never meet. We are divided by racial stereotypes and our society's inability to deal with slavery's impact.

The Livingstons were powerful, wealthy and influential, but instead of being instruments for change, they perpetuated slavery and grew rich using slave labor.

Just as the sweat of the enslaved helped the Livingstons amass a huge fortuune, the wealth of the Western world is built on slavery. The Livingstons and every other white American who has enjoyed the fruits of this system has either directly or indirectly profited from the misery of the enslaved.

How can they say they bear no responsibility for its legacy?

At Clermont, all vestiges of slavery had been buried, hiding the dirty little secrets unearthed by my grandson, secrets of miscegenation and adultery. Philip had a wife named Maria who bore him children. He also had trysts with an enslaved woman named Barbara, for whom he had built a special cabin.

Clermont overlooks the Hudson and the remnants of the pier where Robert Fulton invented the steamboat. General Lafayette on his way to Albany had docked there to enjoy an hour's feast on fresh fruit and rack of lamb.

But there is no slave cemetery at Clermont, which has been a state park since 1962. It seems that there should have been an archaeological dig there to unearth relics, bones and other artifacts that would tell us about the lives of the enslaved who lived and died there.

At this moment, however, the enslaved are out of sight, out of mind. It matters little that slaves helped to build Clermont.

Their work goes unappreciated, and their broken bones, hearts and spirits are long forgotten.

Clermont was the Georgian-style family home of the wealthy and influential Livingstons in upstate New York, and is now a historic site. Its construction was begun by Robert Livingston Jr., whose grandson, Robert R. Livingston Jr., helped to draft the Declaration of Independence. A cousin, Philip Livingston, signed In 1812, Philip Henry Livingston, the grandson of the signer, fathered a daughter by Barbara Williams, an enslaved Jamaican. That daughter was Christiana Taylor Williams, whose great-great-granddaughter is Madeline Wheeler Murphy. Murphy's grandson, Christopher Murphy Rabb, tracked down the lineage.

The Baltimore Sun

Madeline Wheeler Murphy

Daguerreotype courtesy of Christopher Rabb

June 29, 1997

My childhood recollections of the Fourth of July are punctuated by picnics, parades and my father's claim that he was related to one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. My family paid little heed to Pop's claim, and he ** made very little of it. There was no hard proof, just an oral history handed down from his mother.

Although my hometown, Wilmington, Delaware, was segregated, Pop always told us that the Declaration of Independence was an important document. On one particular July Fourth, when I was about 10 years old, I remember him repeating these words in a voice heavy with irony:

"We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness."

No sooner had Pop finished than he uttered an anguished sigh and set off a rocket, which rose toward the heavens and exploded with vengeance. It was if Pop had said, "Take that, you lying s.o.b.'s."

As young as I was, I felt my father's anguish as a "colored girl" attending segregated schools, pools and tennis courts. I was not even allowed to sit in the white movie house balconies, nor at Woolworth's lunch counter for an ice cream soda, not even in the children's room of the public library. Equal, indeed!

After my father had died, the memory of his claim haunted me so much that I asked his sister, Mary Alice Wheeler McNeill, about it. Referring to my great-great-grandmother, she wrote: "Christina Williams was one daughter of a West Indian woman and Philip Livingstone [sic], a member of a prominent New York family."

My aunt wrote her letter in 1950. More than 40 years passed before the relationship between Philip Henry Livingston - the grandson of a signer of the Declaration of Independence - and his enslaved Jamaican, Barbara Williams, was authenticated.

Over the years, I had grown frustrated trying to track down the truth, but my grandson, Christopher Murphy Rabb, a Yale graduate who majored in African and African-American history, was intrigued by the story and confirmed it.

Trying to follow the Livingstons' family tree is very confusing because so many family members have the same or similar names. My aunt said they were "prominent" - which turned out to be an understatement.

By the time the American Revolution began, the Livingston family owned approximately 1 million acres on both sides of the Hudson River in upstate New York.

The empire began when the Crown gave Robert Livingston (1654-1728), the family patriarch, 160,000 acres. When the elder Livingston died, Robert Livingston Jr. (1688-1775) began building Clermont, the Georgian-style family home that is now a historic site.

Robert Livingston Jr.'s only child, Robert R. Livingston (1718-1775), married Margaret Beekman, the heir to some 250,000 acres of land that became part of the Livingstons' holdings. Robert R. Livingston served as judge of the Admiralty Court and judge of the Supreme Court of the Province of New York.

Robert R. Livingston Jr. (1746-1813) is probably the best-known member of the family. He was the eldest son of Robert, the judge, and Margaret Beekman. He also was a member of the Committee of Five that drafted the Declaration of Independence, and he became the first United States minister of foreign affairs (secretary of state). While serving as chancellor of the state of New York, he gave the oath of office to George Washington after he became the nation's first president. Although Robert R. Livingston Jr. helped draw up the Declaration of Independence, he didn't sign it. Philip Livingston, a first cousin once removed, actually signed the document.

In 1812, Philip Henry Livingston, the grandson of the signer of the Declaration of Independence, fathered a daughter by an enslaved woman, Barbara Williams. That daughter was Christiana Taylor Williams (1812 - 1903).

After a yearlong correspondence with a member of the Livingston family, my grandson Christopher found the 1909 Brooklyn, N.Y., copy of Christiana's death certificate. It listed Philip Livingston as her father and Barbara as her mother.

Last year, the descendants of Barbara and Christiana Williams were invited to the Livingston family reunion at the family mansion in Clermont, which is now a state preserve open to the public.

Christopher was invited to make a formal presentation. It was held under a tent that seated 75 to 100 family members, who had mixed reactions to his findings.

Some were curious and asked questions; others averted their eyes and retreated; a few scanned the genealogical charts quietly and spoke to Christopher almost in whispers, obviously embarrassed or uncomfortable with his presentation.

Despite some consternation on the part of a few Livingstons, the local newspaper - ironically called the Kingston Freedman carried a story about the reunion and the Livingstons' black descendants.

It ran with a headline that said: "Mr. and Mrs. Livingston, I presume - Annual reunion in Clermont includes black descendants."

After I arrived at Clermont, I realized that what had been a footnote in my aunt's letter and Pop's sketchy verbal history had come to fore. I rode to the reunion on a lark, but now I had a lump in my throat.

As I stood at the registration desk, putting on my name tag, I realized that I might have been standing where Barbara Williams, my great-great-great grandmother, stood two centuries ago. The registration table sat where some 150 enslaved had been quartered.

Now it was a grassy meadow. All vestiges of slavery with its secrets, graveyards and debauchery had been leveled and buried.

All the jocularity, the sardonic "guess who's coming to dinner" banter had vanished. I felt I was in the center of a whirlpool, enveloped by ghosts.

No government sanctioned apology could assuage the pain I felt for Barbara as a concubine on call whenever Philip lusted after her. Imagine how the other enslaved must have shunned her, taunted her and perhaps even physically attacked her becaused of her relationship with "Massah."

The impact of walking where Barbara had walked and seeing what she had seen took my breath away and churned the pit of my stomach. At the same time, I felt like running away from the ugly truth of my personal proximity to slavery.

Rushing by me, a woman with her child in tow smiled in a patronizing way and asked in the lilting voice mothers use with their children, "Are they treating you all right?"

Out of a daze I mumbled with disdain, "Why wouldn't they?" She became flustered, smiled again, shrugged her shoulders and resumed her walk.

The growing empathy for Barbara was still with me in spirit. Although the woman's question was innocuous, it made me feel like a child who was somehow inferior. I realized that Barbara must have felt the same way much of the time.

I also realized that the woman could not have understood how I felt. Our lives are parallel lines that will never meet. We are divided by racial stereotypes and our society's inability to deal with slavery's impact.

The Livingstons were powerful, wealthy and influential, but instead of being instruments for change, they perpetuated slavery and grew rich using slave labor.

Just as the sweat of the enslaved helped the Livingstons amass a huge fortuune, the wealth of the Western world is built on slavery. The Livingstons and every other white American who has enjoyed the fruits of this system has either directly or indirectly profited from the misery of the enslaved.

How can they say they bear no responsibility for its legacy?

At Clermont, all vestiges of slavery had been buried, hiding the dirty little secrets unearthed by my grandson, secrets of miscegenation and adultery. Philip had a wife named Maria who bore him children. He also had trysts with an enslaved woman named Barbara, for whom he had built a special cabin.

Clermont overlooks the Hudson and the remnants of the pier where Robert Fulton invented the steamboat. General Lafayette on his way to Albany had docked there to enjoy an hour's feast on fresh fruit and rack of lamb.

But there is no slave cemetery at Clermont, which has been a state park since 1962. It seems that there should have been an archaeological dig there to unearth relics, bones and other artifacts that would tell us about the lives of the enslaved who lived and died there.

At this moment, however, the enslaved are out of sight, out of mind. It matters little that slaves helped to build Clermont.

Their work goes unappreciated, and their broken bones, hearts and spirits are long forgotten.

Clermont was the Georgian-style family home of the wealthy and influential Livingstons in upstate New York, and is now a historic site. Its construction was begun by Robert Livingston Jr., whose grandson, Robert R. Livingston Jr., helped to draft the Declaration of Independence. A cousin, Philip Livingston, signed In 1812, Philip Henry Livingston, the grandson of the signer, fathered a daughter by Barbara Williams, an enslaved Jamaican. That daughter was Christiana Taylor Williams, whose great-great-granddaughter is Madeline Wheeler Murphy. Murphy's grandson, Christopher Murphy Rabb, tracked down the lineage.

- Keyboard shortcuts:

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest comments - Subscribe to the comment feeds of this photo

- ipernity © 2007-2024

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter