Blacks on Stage and Screen

Vintage images and bios from stage, film, vaudeville, radio, and early television.

"I didn’t mind playing a maid the first time, because I thought that was how you got into the business. But after I did the same thing over and over, I began to resent it. I didn’t mind being funny, but I didn’t like being stupid."

- Butterfly McQueen

“I never felt the chance to rise above the role of maid in … (read more)

"I didn’t mind playing a maid the first time, because I thought that was how you got into the business. But after I did the same thing over and over, I began to resent it. I didn’t mind being funny, but I didn’t like being stupid."

- Butterfly McQueen

“I never felt the chance to rise above the role of maid in … (read more)

Cleo Desmond

| |

|

Born Matilda Minnie Hatfield in 1888 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She was an actress of stage and screen. Active in the entertainment field from the 1900s til the 1940s. She performed in vaudeville under her original name, first with 'Parson Johnon's Flock,' a big attraction that played Hyde and Behman's Theater in Brooklyn, New York (1901), then with Joseph J Flynn's Nashville Students (a group organized in NYC, not the original famous group founded by P.T. Wright), which toured for a season of fifteen weeks in and around NYC (1902). At what point she joined the Williams & Walker Company is not known, but she toured Europe with that famous troupe (possibly 1902-1908), taking the stage name Cleo Desmond.

In 1909 she performed with Ed Brayer's 'Georgia Campers,' a vaudeville ensemble presenting songs and dances of the South, which played at the Green Point Theater in Brooklyn, NYC. With this act, she and her dancing partner Clarence Bowens, as the team of Desmond & Bowens, performed a so called lazy coon dance. She also performed a solo "song recitations," wearing a seductive, "split to the hips" sheath skirt. Her last recorded vaudeville engagement was in a sister act, billed as Desmond & Bailey (partner unknown), a performance of songs and monologues, which played at the Columbia Theater in NYC (1909).

Beginning in 1916, as a former member of the Anita Bush All-Colored Dramatic Stock Company she became a member of the original company of Lafayette Players at the Lafayette Theater in Harlem, NYC, where she soon established herself as one of the company's featured players (circa 1916-1922), best remembered for her role as the landlady in Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

She performed in several all-Black films of Oscar Micheaux. In 1938 she performed in the Los Angelos production of Hall Johnson's 'Run Little Chillun!'

She died in 1958, in San Diego, at the age of 70.

Sources: The Competitor vol. 1, 1920 ; Profiles of African American Stage Performers and Theatre People, 1816-1960 by Bernard L. Peterson

Belle Davis

| |

|

Belle Davis was an African American song and dance artist, entertainer, choreographer, and director. She was a recording pioneer who toured Europe extensively during the period 1901-1929. Not only did she record on disc as early as 1902, she also performed in front of a movie camera at least twice during the early years of this century. In spite of these extraordinary achievements, little has been written about her; her biography, her discography and her filmography remain sketchy.

Belle Davis, (1874 - circa 1938), was born in Chicago, Illinois on April 28, 1874, the daughter of George Davis. Of European and African ancestry, she spent most of her adult life abroad, largely in Britain, where she arrived in mid-1901 with two boys who were billed as Piccaninny Actors. Her performance style changed from ‘coon shouting’ and ‘ragtime singing’ in the 1890s to a more decorous manner, where prancing children provided the amusement. She directed their stage act, and with two, sometimes three or four, black children the act was a vigorous and popular entertainment in British and continental theatres.

Davis's troupe appeared on the reputable Empire Theatre circuit in late 1901, recorded in London in 1902 (including the song ‘The Honey-Suckle and the Bee’), continued touring London and the provinces in 1903, and ventured to the continent. Dozens of other African-Americans were entertaining the British at this time, and on June 9, 1904 Davis married one of the more successful, Henry Troy, in London. Following her marriage the act continued to tour, and was filmed, for commercial distribution. The Empire circuit continued to employ the group, as did other leading theatres. They presented their ten-minute stage act in Dublin, Cardiff, Swansea, Manchester, Birmingham, Nottingham, Leicester, Edinburgh, Liverpool, and Sheffield between May 1906 and August 1909, and appeared in Berlin, The Hague, Paris, Vienna, St Petersburg, and Brussels during the same period. Some leading performers had their apprenticeship as dancers in Davis's act; when they grew too large she recruited younger boys from America.

The act had been seen by hundreds of thousands of Britons by 1914, when war prevented continental touring and so exposed more Britons to Belle Davis and Her Cracker Jacks. She and the children performed in major cities as well as Ayr, Doncaster, Portsmouth, Ilkeston, and Weymouth during the war years. Her last known performance in Britain was in 1918. From 1925 to 1929 she directed the dancing in the revues at the Casino de Paris, and 1929 also saw Belle Davis Piccaninnies in Germany with Wunderland der Liebe, a revue set in the south seas. As early as 1915 she was describing herself as married to the African American entertainer Edward Peter (Eddie) Whaley (circa 1880–1960), and she took out an American passport in the name Belle Whaley in 1920. She and Whaley eventually did marry, on July 12, 1926, but they had divorced by 1936. In 1938 she boarded the Queen Mary in Southampton to return to a Chicago address.

Sometimes billed as a ‘creole’, Davis was a soprano whose songs were not from the minstrel show or spiritual traditions, but were graceful melodies. By contrast the children were energetic dancers who combined suppleness with comedy. Their well-dressed director's elegance was praised, and is evidenced by surviving promotional material. The mercurial entertainment business had few acts for whom top theatres provided employment for the length of time she worked in Britain. Her qualities both as a singer and as dance director, combined with her professionalism in travelling from town to town, country to country, in charge of boisterous children, were solid, and enabled her to have success at her chosen profession for three decades. Stately, well dressed, and showing faint African features, she presented American dance and song to countless Britons and kept top employers anxious to take her act for their shows.

Sources: Jeffrey Green and Rainer E. Lotz

Maude Russell

| |

|

New York Times

March 29,2001

by Joyce Wadler

Maude Rutherford, 104, Dies

High-Kicking Songster of 1920's

Maude Russell Rutherford, a singer and dancer in the glory days of black theater in the 1920's who always said she was the one who really introduced the Charleston on Broadway, died on March 8 at her home in Atlantic City. She is believed to have been 104.

Strikingly pretty, she was billed as the Slim Princess when she worked with Josephine Baker, Fats Waller and Pearl Bailey. Never a star, Ms. Rutherford was usually the soubrette or a featured performer and a great favorite at Harlem's Cotton Club.

She wrote her particular footnote to history in 1922 in the Broadway show ''Liza, '' an all-black revue with lyrics and music by Maceo Pinkard. While many dance histories credit the 1923 show ''Runnin' Wild'' with bringing the Charleston to Broadway, Ms. Rutherford led the ''Liza'' chorus girls in the dance a year earlier.

She remained proud of her dance abilities to the end of her life.

''I used to kick 32 times across the stage, and my legs would hit my nose,'' Ms. Rutherford told Jean-Claude Baker, who was reared by Josephine Baker and who is a student of black entertainment. ''I was a dancing fool.''

Ms. Rutherford was born in Texas to a black mother, Margaret Lee, and a white father, William McCann. With interracial unions prohibited, her parents never lived together.

As a teenager working as a ticket taker, Ms. Rutherford met Sam Russell, a star of the black theater with the comedy team Bilo and Ashes. He asked her to go on the road with him. She demanded marriage first. The marriage was violent and short. Ms. Rutherford, weary of being beaten, surreptitiously relieved her husband of $100, then struck out on her own.

Tall, with a sweet voice, she would play the bouncy, good-time girl, perhaps the comic relief. ''I'm Forever Blowing Bubbles'' was a youthful audition choice. Early in her career a producer tried to mold her as a blues singer, but, as Ms. Rutherford told Mr. Baker in a taped interview, it did not fit. The producer said, ''Honey, you stick to bubbles.''

Her style offstage was down to earth and no-nonsense, and she used language too vivid to be called plain-spoken; she described one colleague as ''so ugly she could take a stick and break day.''

Ms. Rutherford's theater credits included ''Dixie to Broadway'' (1924), ''Chocolate Scandals'' (1927) and ''Keep Shufflin' '' (1928). She left show business in the 1950's and in 1953 married her fifth husband, Septimus Rutherford, chief steward for the Moore-McCormack Lines. She worked as a switchboard operator in an Atlantic City hotel.

But she never lost her show-biz flair.

When her husband died in 1980, Ms. Rutherford had her name carved into the headstone she and her husband would share, as well as a birth date, Mr. Baker said.

But instead of 1897, which she had told friends was the year of her birth, the carved date was 1902.

''She said, 'By the time I die, nobody will be here to remember, so I will go forever in eternity five years younger,' '' Mr. Baker said.

Jean-Claude Baker Foundation

Aida Ward

| |

|

Aida Ward (1903 - 1984), was a nightclub, stage, and radio singer in the 1920s and 1930s who popularized the hit song, "I Can't Give You Anything But Love, Baby" and "I've Got The World On A String."

Her professional career began on Broadway in 1924 as a featured singer in the musical "Dixie to Broadway." The production was a star vehicle for Florence Mills. It was the first all-Black show to have a mainstream Broadway production.

Known as the "prima donna" of the Cotton Club in Harlem, she was already a star in her own right when she became successor to the great entertainer Florence Mills. And was featured vocalist with the Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway orchestras. She was a headliner at the Cotton Club when she befriended Lena Horne, who was 17 at the time and a novice chorus girl.

She appeared in New York, London and Paris in the hit play Blackbirds (1926-27 run), and, after Florence Mills death, shared star billing in Blackbirds of 1928 with singer Adelaide Hall.

She also sang on national radio programs.

She retired from show business in the late 1940s and returned to Washington where she operated a nursing home. She retired for the second time in 1969.

Miss Ward, a graduate of Dunbar High School, was a member of the Seventh Church of Christ Scientist in Washington, where she was active on the music committee.

Her marriages to Walter Gist and Edward Chavers ended in divorce. A son by her first marriage, Jerome Gist, died in 1983. Survivors include one grandchild.

Her final days were spent in a nursing home in her native Washington DC., where she died at the age of 84 of respiratory problems at Howard University Hospital.

Source: Washington Post

Anna Madah Hyers

| |

|

Anna Madah Hyers was regarded as the first black woman to enter the concert world. She paved the way for many prosperous black concert singers like Marian Anderson, Paul Robeson, and Leontyne Price.

Born in Sacramento, California in 1856, Hyers spent much of her childhood studying music with her father, Sam Hyers, a musician, and with German music professor Hugo Sank. Together they transformed Hyers' immature soprano voice into an angelic powerhouse.

In 1867, Hyers made her professional debut at the Metropolitan Theater in Sacramento with her younger sister Emma Louise. Because the sisters shared the same talent, they would occasionally sing duets. Their performances were a success and ensured them a leading position among the prima donnas of the age. In 1871, the Hyers sisters performed their first major recital.

The Salt Lake Theater in Utah welcomed them along with baritone Joseph LeCount. Anna's soprano, Emma's alto tenor and LeCount's baritone sounded so riveting in harmony that they left the audience wanting more. Soon after the successful recital in Salt Lake City, the Hyers sisters were encouraged to launch a national tour. Following the tour, they formed the Hyers Sisters Concert Company, which performed concert music and staged musical comedies. Some of the most recognized productions were "Out of Bondage" (1875), "Urlina, or The African Princess" (1877), and "Colored Aristocracy" and "The Underground Railroad," which were both introduced in 1879. The production company faded after her younger sister Emma's death in 1899. Yet Anna continued singing and touring the United States with other production companies until her retirement in 1902. She died in Sacramento, California of a heart ailment in 1925.

Info: Pittsburgh Post Gazette , by Angela Dyer (March 1999), Photo: Stella Wiley's Scrapbook

Lily Yuen

| |

|

Born around 1902, Lily Yuen grew up not in Shanghai, China, but in Savannah, Georgia, and was famous during the 1920s and 30s as a dancer, singer, and comedienne. Beneath a headline proclaiming her “A Racial Puzzle,' an article in The Afro-American (June 20, 1925 edition) revealed that “Miss Lily Yuen, a tall, agile, brown girl ... is typically Negro, and yet she is the daughter of a Chinese subject and of a colored woman." It went on to say that her father was an immigrant from China named Ton Yuen [also known as Joe Yuen] who settled down in Savannah, opened a laundry business, and married an African American woman [named Josephine, also known as Josie].

Lily started dancing professionally in 1922 and a year later was performing with Jones’ Syncopated Syncopators, an African American vaudeville revue led by Joseph Jones, who was known as “the best Jewish impersonator among colored actors” (The Afro-American, October 5, 1923). She soon earned a reputation for her Charleston strut and “eccentric” dance steps which left audiences clamoring for encore after encore.

In 1926 she joined Irvin C. Miller’s “Brown Skin Models” revue, billed in newspaper advertisements as “The Greatest Array of Colored Stars Ever Assembled” and “The Ziegfeld Follies with a Palm Beach Tan”. Lily was one of the show’s leading attractions and “a fully recognized star in her line and exceptionally in the Charlestonian realm” (Pittsburgh Courier, February 13, 1926).

By the end of 1927 Lily had left “Brown Skin Models” to form her own trio called the Three Dance Maniacs. The next year a short profile of Lily appeared in the Pittsburgh Courier (December 8, 1928), summing up her successful career thus far: Fifty Thousand Dollar Legs ... This may be only a small part of the real value of the shapely dancing limbs of one Lily Yuen, good looking, fine personality and a stage favorite wherever she puts on her large flat shoes, sweater and cap that rests at a saucy angle upon her pretty tresses. Miss Yuen has been dancing about five years. Reaching efficiency of a charming type which placed her on many bills in big time white houses, where she never failed to score. Sometimes she works in a trio other times alone. But at all times she is earnest and a hard worker. She originates all her steps, many of which are now being copied and used by Broadway white girls.

Around this time Lily settled down in New York and during the next few years performed in such shows as “Ginger Snaps of 1929”, “Fidgety Feet”, “S’prise Me!”, and “Jazz-Mad”. She continued performing throughout the 1930s, including a stint with Ethel Waters in 1938. Lily was reported to have married in 1941, but that didn’t seem to stop her career. In 1946 she was headlining nightclubs in Baltimore and Washington D.C.

She was interviewed in the 1980s and told of how she once shared an apartment with several chorus girls one of whom was Josephine Baker. “People always say she was in the Cotton Club,” Lilly complained. “Josephine wasn’t in no Cotton Club. She was just a chorus girl, baby, we all was chorus girls.”

At this point I have yet to find a death notice or obituary for Ms. Yuen.

Sources: Penn Studio; softfilmblogspot, by duriandave

Oriental Opera Company

| |

|

Mr. Graffe, a millionaire from Syracuse, New York, wanted to prove to the world that Negroes could sing opera music as well as folk songs and financed for one year a company known as the Oriental Opera Company . Madam Plato and Sidney Woodward were the star singers and Mr. J. Rosemond Johnson was the musical director. Miss Eartha M. White, a lyric soprano from the National Conservatory of Music, was accepted as a singer. They opened at the Palmer Theater on Broadway in New York City and proved to be so successful that they traveled for one year in the United States and Europe. The above photograph is from 1893.

Source: Eartha M M White Collection

Semoura Clark

| |

|

Semoura Clark, was a vaudevillian, who along with her sometime stage partner 'Bonnie' Clark (who was actually a male in drag) provided segregated entertainment for blacks in the South and Midwest. Photographs and ephemera from the Bonnie and Semoura Clark contains photographs and ephemera depicting predominantly black vaudeville acts including photographs of chorus girls, minstrels, and cross dressers, handbills and programs and two ink and wash drawings of Bonnie and Semoura Clark, dated 1913. Other popular entertainments competed with the vaudeville theater circuits for the attention of the American public. Long before the addition of kooch dances and striptease, early burlesque shows were famous for their “lady minstrels” and grand choruses of girls In flesh-colored tights. The burlesque stage was also known for its comic parodies of classical and popular drama and its own version of the full-cast finale, known as the Amazon parade.

In popular plays of the period, realism was the vogue. To effect a sense of reality, real objects and animals were substituted for stage props; all manner of things appeared on stage—from horses to trees to fire engines. One company performing Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin boasted the appearance of real hunting dogs. Historic events in the expansion of the America West were reenacted on stage as western melodramas by the Buffalo Bill Combination, led by the famous frontiersman, William F. Cody. These sensational, if often historically inaccurate, popular stage shows were soon moved to outdoor arenas. Wild West shows became a staple in American entertainment, but the most famous by far was Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show.

Ruckus! American Entertainments at the Turn of the Twentieth Century and the Bonnie and Semoura Clark Black Vaudeville Collection recall these popular divertissements in all their variety and vivacity and celebrates the performers, both the famous and the forgotten, who were at the heart of the period’s most lively amusements.

Sources: Bonnie and Semoura Clark Black Vaudeville Photographs and Ephemera. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the American Literature Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

Opportunity

| |

|

April, 1933 edition of 'Opportunity' with actress Fredi Washington on the cover. University of Minnesota Libraries, Archie Givens, Sr. Collection of African American Literature .

The monthly magazine Opportunity gave just that—a chance to make their voices heard—to the talented black writers of the Harlem Renaissance.

Created in 1923 by the National Urban League (a group devoted to empowering African Americans economically and socially), Opportunity was edited by scholar Charles S. Johnson. In Johnson's deft hands, Opportunity became a tool for combating racism. During an era when African Americans routinely struggled to land decent jobs, Johnson strove to introduce white audiences to the work of gifted black writers and artists. Expanded social roles and employment opportunities for African Americans, he reasoned, would follow.

Another purpose of Opportunity was to promote the programs and policies of the Urban League. In addition to a report of pertinent news, the magazine’s regular departments included “Social Progress,” “Our Negro College,” “Labor,” and the “Survey of the Month,” as well as notes on black accomplishments in the arts and professions. Although Opportunity sought to inform and instruct its readers on the social and economic condition of the race, and only secondarily on political issues, there was a decidedly literary character to the publication. James Weldon Johnson, Helene Johnson, Alain Locke, Langston Hughes, and, for a short time, Claude McKay were but a few of the frequent contributors to the magazine. Countee Cullen and Gwendolyn Bennett each served for a period as literary critic in the 1920s, and in the 1930s Sterling Brown of Howard University wrote the monthly column “The Literary Scene.”

To make sure the mainstream publishing world learned that Opportunity was knocking, Charles S. Johnson hosted a lavish dinner at New York City's Civic Club in 1924. With scholar Alain Locke presiding as master of ceremonies, the grand affair mixed prominent publishers and magazine editors with up-and-coming black writers. This momentous event resulted in the publication of Countee Cullen's poems by Harper's magazine, as well as a Survey Graphic magazine dedicated to works by the "New Negro." The Civic Club soirée was just the first of many award ceremonies that Opportunity would host in its ongoing celebration of the spectrum of black talent. The magazine ended its publication in 1949.

Source: Drop Me Off in Harlem: Exploring the Intersections; Northwestern University Library

William D Foster

| |

|

The Foster Photoplay Company was the first black film company (which was located at 3312 Wabash Avenue), was formed in 1909 and put out two shorts The Pullman Porter (1910), and The Railroad Porter (1912), which are often credited as the first films directed by a black director with an entirely black cast.

Synopsis of 'The Railroad Porter' : Its a short comedy about a railroad porter who leaves to go on his run one day. In his absence, his wife invites a waiter from a colored cafe on State Street home for dinner. The porter returns unexpectedly to find another man sitting at his table and eating his food! Mad and insulted, the porter gets his pistol and chases the man out of his house. The waiter goes and gets his gun, comes back, and chases the porter. Fortunately, both are terrible shots and no one gets hurt. [Actors: Lottie Grady (wife), Jerry Mills (porter), and Edgar Litterson (waiter)].

The film's style has often been compared to that of the Keystone Kops comedies of the same period.

William D. Foster (circa 1860 - 1940), was the first African American to found a film production company. Writing under the name Juli Jones, Foster began his career as a sports writer for the Chicago Defender, then a local African-American newspaper, that had recently been established in 1905 by Robert Sengstacke Abbott, which quickly became the nations “most influential Black weekly newspaper.” Foster periodically wrote for other newspapers including the Indianapolis Freeman, where he published an article on “the public discourse on the representation of blacks in white-produced films.” Foster was also a press agent for vaudeville stars such as Bert Williams and George Walker and their revues, as well as worked as a booking agent and business manger for Chicago’s Pekin Theater, a well known vaudeville house. He is known to have incorporated various techniques from other films into his productions, as well as successful comedy elements from the black vaudeville stage. He was a multitalented man who intertwined many careers in the course of his life.

Moving pictures had barely crept out of the nickelodeon to dance upon the silver screen when Foster grasped the profit potential in this new and exciting medium. At the time, the portrayal of Blacks was nothing less than reprehensible. Even the titles of early films like A Nigger in the Woodpile and the degrading classic The Watermelon Contest demonstrated loathing and disrespect for Blacks, and did not try to hide their racist intent.

In 1910, Foster started Foster Photoplay Company in Chicago and set about taking control of the black image into his own hands. He had often booked vaudeville acts for the Robert Mott's Peking Theater Stock Company, and he turned to that pool of talent for his actors. Two years later, The Railroad Porter, was in the can and Foster would produce three more motion pictures in the year that followed.

In 1914, to help promote his previous success, Foster toured the South with a retrospective of the four Foster Photoplay short films. The Railroad Porter, The Fall Guy (1913) another comedy, The Butler (1913) a melodrama. As part of the program, Lottie Grady, the company's leading lady, would sing and entertain between reel changes.

Despite seeing a positive response to his films, and receiving praise for their positive, realistic depictions of black characters, he failed to experience the same level of success as his primarily white competitors. While white-owned production companies received coverage and advertising placement in trade paper publications, the only coverage Foster received was as the result of calling up the Moving Picture World offices himself. He described his productions in detail to the staff writer, saying, “I don’t want you to take my word for it that these comedies are a big hit. I just want you to come and see one of them and laugh your head off.”

A lack of attention from the mainstream trade publications, and an inability to help advance the company further pushed Foster to close the Foster Photoplay Company in 1917. Although he continued to write for a number of publications, he also returned to the world of film, acting as an assistant director in Hollywood in the 1920s. He died in Los Angeles, California in 1940.

The history of race films began with Foster and provided an opportunity for African-Americans to depict their own image in the way they wanted. The Foster Photoplay Company paved the way for Lincoln Motion Picture Company (1915) and Ebony Film Corp. By the 1920s, more than thirty film production companies had been set up to produce films about blacks and black life.

Sources: 50 Most Influential Black Films: A Celebration of African-American Talent, Determination, and Creativity by S. Torriano Berry with Venise T Berry; chicagonitrate.com; Arts & Critiques Blogspot, by Kristen aka Miss Arts Critic

George Walker

| |

|

"We want our folks the Negroes, to like us. Over and above the money and the prestige is a love for the race. We feel that in a degree we represent the race and every hair's breadth of achievement we make is to its credit." (George Walker, 1909)

He was 1/2 of the famous vaudeville team Williams and Walker ... George Nash Walker, (b.1873 - d.1911) was born in 1873 in Lawrence, Kansas. He left at a young age to follow his dream of becoming a stage performer and toured with a traveling group of minstrels. After performing at shows and fairs across the country, Walker met Bert Williams in 1893 and they formed the duo known as Williams and Walker. During this time, white men performing in minstrel shows blackened their faces to pose as black performers. As a counter, Williams and Walker billed themselves as “Two Real Coons,” a descriptor that marked the two as black men and a reference to the derogatory term “coon” used to describe people of African descent in the United States. While performing as a vaudeville act throughout the United States, George Walker and his partner Bert Williams popularized the cakewalk, an African American dance form named for the prize that would be earned by the winners of a dance contest.

There was a distinct difference in presentation styles between the two performers. While the light skinned Bert Williams donned blackface makeup, George Walker was known as a “dandy” who performed without makeup. While Williams played the role of the comic figure, George Walker played the straight man, a dignified counterpoint to the prevailing negative stereotypes of the time. Offstage, Walker was an astute businessman who managed the affairs of the Williams and Walker Company, a venture that brought them fame and wealth nationally and internationally. In 1903, they performed In Dahomey at Buckingham Palace in London and then toured the British Isles.

Working in collaboration with Will Marion Cook as playwright, Jesse Shipp as director, and Paul Laurence Dunbar as lyricist, Williams and Walker produced a musical called In Dahomey in 1902. In this play, with its original music, props, and elaborate scenery, Walker played a hustler disguised as a prince from Dahomey who was dispatched by a group of dishonest investors to convince blacks to join a colony. A landmark production, In Dahomey was the first all black show to open on Broadway. Another musical, In Abyssinia opened in 1906 in New York at the Majestic Theater. Both of these productions used African themes and imagery, making them unique for the time. Other Williams and Walker productions include: The Sons of Ham (1900), The Policy Players (1899), and Bandana Land (1908).

George Walker married Ada (Aida) Overton, a dancer, choreographer, and comedienne in 1899. Ada (Aida) Overton Walker was known as one of the first professional African American choreographers. After falling ill during the tour of Bandana Land in 1909, George Walker returned to Lawrence, Kansas, the city of his birth where he died on January 8, 1911. He was 38.

Sources: Louis Chude-Sokei, The Last “Darky”: Bert Williams, Black-On-Black Minstrelsy, and the African Diaspora (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006); Photographed by Morris of Lawrence Kansas; railsplitter

Griffin Sisters

| |

|

Publicity photograph from The Freeman, An Illustrated Colored Newspaper , Sept. 10, 1910 edition. Mabel on the left and Emma on the right.

Mabel (circa 1870 - ?) and Emma Griffin (1873 - 1918), were born in Louisville, Kentucky. They were the highly popular vaudeville performers known as The Griffin Sisters who toured throughout the United States. They began performing as members of John Isham's Octoroons Company and toured with several other companies before organizing their own theater booking agency in 1913 in Chicago. They had been considered premiere performers and broke theater attendance records while with the Sherman H. Dudley agency, created in 1912 as the first African American operated vaudeville circuit. The Griffin Agency was one of the earliest to be managed by African American women, and they also had a school of vaudeville art. Emma Griffin encourage African American performers to use either the Dudley Agency or the Griffin Agency. The sisters also opened the Alamon Theater in Indianapolis, Indiana, in April of 1914. They managed the Majestic Theater in Washington, D.C. in June of 1914. The sisters were listed as mulattoes, along with their brother Henry, who was a musician, and their grandmother Mary Montgomery, all in the 1910 Census when the family lived in Chicago. [Bio: Dictionary of Afro-American and African Musicians , by E. Southern]

The Griffin sisters were also way ahead of their time ... they didn't cower quietly when mistreated. The following is an article in the San Francisco Call Newspaper dated, February 21, 1906:

Two Colored Women Experience Difficulty in Getting Assailant Into Court Two colored women known in cheap, vaudeville as the Griffin sisters, Emma and Mabel, sought to have one "Billy" Pratt, a Mason street saloon-keeper, arrested on their charge of battery. They unfolded their complaint to Deputy Clerk George M. Kelly, sablewhiskered and very voluble, who informed them that the best he could do would be to request the accused to appear before him and opine whether or not a warrant should be issued. And to show that he could do that much Mr. Kelly wrote a politely worded note to Mr. Pratt and gave it to the women to deliver, despite their assertion that they were afraid they might be battered again if they confronted him. Then they were told that if they did not desire to convey, the message they might entrust Its delivery to the policeman on the beat.. When a bystander questioned Mr. Kelly's authority to act as he did the explanation was given that Judge Shortall had been asked to issue the desired warrant, but had declined to do so on the ground that Mr. Pratt was one of his personal friends and that he could not try the case without prejudice. "Then," said the meddler to Mr. Kelly, "why don't you advise the women to lay their case before one of the other Judges?" Mr. Kelly said a great deal in reply without giving logical answer to the question, and he was still talking when the interrogator went and obtained Judge Mogan's promise that he would sign the warrant.

When this was stated to Mr. Kelly he declared that he would not frame the warrant unless he received Judge Mogan's written order to do so. Instead of going back to Judge Mogan, however, the busybody escorted the women to Judge Cabaniss, who heard their story and instantly signed an order that the warrant be issued. But when the trio returned with the order it was the chief of the office instead of Mr. Kelly, who took it and after considerable delay complied with it. "By what right," Mr. Kelly was asked, "does this office undertake to decide whether a warrant shall be issued?' "We do it," replied Mr. Kelly, "to relieve the Judges from the trouble of hearing applications for warrants." "But it is the prescribed duty of the Judges to experience the trouble you allude to, isn't it?" "Well, we have made a rule and we are sticking to it." said Mr. Kelly. "We don't issue a warrant for misdemeanor until we have given the accused opportunity to tell us his or her side of the story." "Thereby you .constitute, this office a. tribunal and usurp the work of the' Police Judges, don't you?" "We have made the rule and we're sticking to it," replied Mr. Kelly. "Thus it has come to pass that charges of misdemeanor are tried and decided by the Warrant Clerk or any of his deputies Instead of by a magistrate duly authorized by the charter to perform that duty. The Griffin sisters are evidently skaters In stageland only, for (Emma's countenance is, several degrees duskier than that of Mabel, whose hair is slightly "kinked and deeply dyed a beautiful antique gold hue").

They claim to have delighted large and cultured audiences in almost every city and town of considerable note, on the Pacific Coast and that they are always headlined on the bills as "Character Change Artists and Entrancing Vocalists." They were en route from a theater to their joint abode night before last when a masculine admirer of their art invited them to partake of liquid refreshments in Mr. Pratt's saloon, and their acceptance of the invitation led *to the alleged battery by Mr. Pratt, who, apparently drew the color line in his treatment of patrons." Mable displayed a lacerated lip and alleged that it was caused by Mr Pratt striking her with a wine glass as he forcibly ejected her and Emma from his refectory.

The article ends here ... I have no idea if Pratt was ever charged or prosecuted with assault.

Black Herman

| |

|

Benjamin Rucker (1892 - 1934), was born in Amherst, Virginia. He met a white traveling magician, Prince Herman, who taught him magic and eventually took him on as a partner. Rucker learned how to make the "health tonic" they sold as part of the show and how to put on a successful show. When Prince Herman died in 1909, Rucker continued the show and took the name Black Herman, eventually settling in Harlem, New York.

Using a combination of medicine show techniques, references to a fictional childhood in a Zulu tribe in Africa, and a taste for quoting scripture, Rucker found the performance style that worked for him. He let audience members tie him up so he could demonstrate how "If the slave traders tried to take any of my people captive, we would release ourselves using our secret knowledge."

Rucker's work depended on travel from city to city to gain his fan base. When he traveled to northern states, he could perform for a racially mixed audience, which was unheard of for most towns, but in the South, he was heavily subjected to Jim Crow laws and only allowed to perform for blacks. Witnessing segregation, he became an advocate for civil rights and a freedom fighter, holding roundtable meetings at his home in Harlem and planning ways to fight the oppression.

By 1923, Rucker had added "Buried Alive" to his act. At first, he would "hypnotize" a woman and then bury her six feet under for almost six hours as a publicity stunt or part of a carnival. Eventually, he himself was "Buried Alive." A few days before a major performance, Rucker would sell tickets for the public to come to a plot of ground near the theater he called "Black Herman's Private Graveyard". They could view his lifeless body and even check for a pulse—nothing. The audience would then see Black Herman's body placed in a coffin and into the grave. The night of the show, another audience was invited to attend as the body was exhumed. They saw the coffin get dug up, opened, and Rucker would emerge, alive and well. He would then walk to the theater, and the audience usually followed.

In April, 1934, Rucker was performing in Louisville, Kentucky. He collapsed suddenly in the middle of his show and was declared dead of "acute indigestion." The audience didn't believe it. Black Herman had risen from the dead so many times before. The crowd refused to believe that the show was over and stayed in the theater.

Eventually Rucker's body was moved to a funeral home. The crowds followed. Finally, Black Herman's assistant, Washington Reeves, decided "Let's charge admission. That's what he would have done." And they did, to thousands of people. Some people even brought pins to stick in the corpse to prove he was dead. When he was buried, "his death made front page news in black newspapers all over the country."

Source: magicexhibit.org

Orpheus M McAdoo

| |

|

Orpheus McAdoo was born in Greensboro, North Carolina on January 4, 1858. He graduated from Hampton Institute in 1876, and taught school in rural Virginia for three years and then at the Hampton preparatory school for several years. In 1885, McAdoo joined Frederick Loudin's Jubilee Singers, also known as the Original Fisk Jubilee Singers, and toured with the group in London and Australia. He returned to the United States in 1889 to form his own group, the Virginia Concert Company and Jubilee Singers. Among the people he recruited were Belle F. Gibbons, his younger brother Eugene McAdoo, Madame J. Stewart Ball, his future wife Mattie E. Allen, and Moses Hamilton Hodges.

Mattie E. Allen was born in Columbus, Ohio, circa 1868. After graduating from high school, she taught school, before joining Orpheus McAdoo's Virginia Concert Company and Jubilee Singers as a contralto soloist. She married McAdoo in 1891, and gave birth to a son, Myron, in 1893.

Beginning in 1890, the McAdoos' Virginia Concert Company and Jubilee Singers toured the British Isles before traveling to South Africa, where they had a great deal of success, performing in large cities as well as more remote regions of the country from 1890 to 1892. In 1892, the company embarked on a tour of Australia and New Zealand. They returned to South Africa in 1895 for a second extended tour, at which point McAdoo transformed the group from the Virginia Concert Company and Jubilee Singers to McAdoo's Minstrel and Vaudeville Company and broadened the list of performers to include variety artists in addition to singers.

McAdoo's company headed back to Australia in 1898. While the company toured Australia, McAdoo returned to the United States in 1899 to assemble a full-scale modern African American minstrel troupe, which he named the Georgia Minstrels and Alabama Cakewalkers. The newly-formed company toured Australia from 1899 to 1900. Six weeks after the end of the tour, on July 17, 1900, McAdoo died and was buried in Waverly Cemetery, Sydney.

African American Studies at Yale, Beinecke Collection

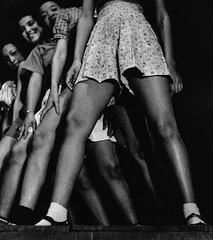

Rehearsal for a chorus line at the Apollo Theater

| |

|

Young African American women (names unknown) rehearse for the chorus line at the Apollo Theater in Harlem. Lucien Aigner, Photographer

Since opening its doors in 1914 and introducing the first Amateur Night contests in 1934, the Apollo has played a major role in the emergence of jazz, swing, bebop, R&B, gospel, blues, and soul — all quintessentially American music genres. Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan, Billie Holiday, Sammy Davis Jr., James Brown, Bill Cosby, Gladys Knight, Luther Vandross, D’Angelo, Lauryn Hill, and countless others began their road to stardom on the Apollo stage. Today, the Apollo is a respected not-for-profit, which presents concerts, performing arts, education and community outreach programs.

The neo-classical theater known today as the Apollo Theater was designed by George Keister and first owned by Sidney Cohen. In 1914, Benjamin Hurtig and Harry Seamon obtained a thirty-year lease on the newly constructed theater calling it Hurtig and Seamon’s New Burlesque Theater. Like many American theaters during this time, African-Americans were not allowed to attend as patrons or to perform.

In 1933 Fiorello La Guardia, who would later become New York City’s Mayor, began a campaign against burlesque. Hurtig & Seamon’s was one of many theaters that would close down.

Cohen reopened the building as the 125th Street Apollo Theatre in 1934 with his partner, Morris Sussman serving as manager. Cohen and Sussman changed the format of the shows from burlesque to variety revues and redirected their marketing attention to the growing African-American community in Harlem.

Frank Schiffman and Leo Brecher took over the Apollo in 1935. The Schiffman and Brecher families would operate the Theater until the late 1970s.

The Apollo reopened briefly in 1978 under new management then closed again in November 1979. In 1981, it was purchased by Percy Sutton a prominent lawyer, politician, media and technology executive, and a group of private investors. Under Sutton’s ownership, the Theater was equipped with a recording and television studio.

In 1983, the Apollo received state and city landmark status and in 1991, Apollo Theater Foundation, Inc., was established as a private, not-for-profit organization to manage, fund and oversee programming for the Apollo Theater. Today, the Apollo, which functions under the guidance of a Board of Directors, presents concerts, performing arts, education and community outreach programs.

Source: apollotheater.org

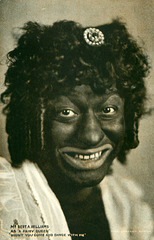

Image Speak

| |

|

The image is of Bert Williams, first black star of vaudeville.

Here is as a caricature to please the masses. To make us more palatable to their tastebuds.

Facing Racism : Racial prejudice shaped Williams' career. Unlike many other blackface performers, Williams did not play for laughs at the expense of other African Americans or black culture. Instead, he based his humor on universal situations in which any members of his audience might find themselves. In the style of vaudeville, Williams performed in blackface makeup like his white counterparts. Blackface worked like a double mask for him. It emphasized the difference between Williams, his fellow vaudevillians, and his white audiences.

People sometimes ask me if I would not give anything to be white. I answer, in the words of the song, most emphatically, “No.” How do I know what I might be if I were a white man? I might be a sand-hog, burrowing away and losing my health for eight dollars a day. I might be a street-car conductor at twelve or fifteen dollars a week. There is many a white man less fortunate and less well equipped than I am. In truth, I have never been able to discover that there was anything disgraceful in being a colored man. But I have found it inconvenient—in America. How many times have hotel keepers said to me, ‘I know you, Williams, and I like you, and I would like nothing better than to have you stay here, but you see we have “southern gentlemen” in the house and they would object.’ Frankly, I can’t understand what it is all about. I breathe like other people, eat like them - if you put me at a dinner table you can be reasonably sure that I won’t use my ice cream fork for my salad; I think like other people.I guess the whole trouble must be that I don’t look like them. They say it is a matter of race prejudice. But if it were prejudice, a baby would have it, and you will never find it in a baby. It has to be inculcated on people. For one thing I have noticed that this ‘race prejudice’ is not to be found in people who are sure enough of their position to be able to defy it. For example, the kindest, most courteous, most democratic man I ever met was the king of England, the late King Edward VII. - Bert Williams

Aida Overton Walker

| |

|

Aida Overton Walker (1880-1914), dazzled early 20th century theater audiences with her original dance routines, her enchanting singing voice, and her penchant for elegant costumes. One of the premiere African American women artists of the turn of the century, she popularized the cakewalk and introduced it to English society. In addition to her attractive stage persona and highly acclaimed performances, she won the hearts of black entertainers for numerous benefit performances near the end of her tragically short career and for her cultivation of younger women performers. She was, in the words of the New York Age's Lester Walton, the exponent of "clean, refined artistic entertainment."

Born in New York City, where she gained an education and considerable musical training. At the tender age of fifteen, she joined John Isham's Octoroons, one of the most influential black touring groups of the 1890s, and the following year she became a member of the Black Patti Troubadours. Although the show consisted of dozens of performers, Overton emerged as one of the most promising soubrettes of her day. In 1898, she joined the company of the famous comedy team Bert Williams and George Walker, and appeared in all of their shows—The Policy Players (1899), The Sons of Ham (1900), In Dahomey (1902), Abyssinia (1905), and Bandanna Land (1907). Within about a year of their meeting, George Walker and Overton married and before long became one of the most admired and elegant African American couples on stage.

While George Walker supplied most of the ideas for the musical comedies and Bert Williams enjoyed fame as the "funniest man in America," Aida quickly became an indispensable member of the Williams and Walker Company. In The Sons of Ham, for example, her rendition of Hannah from Savannah won praise for combining superb vocal control with acting skill that together presented a positive, strong image of black womanhood. Indeed, onstage Aida refused to comply with the plantation image of black women as plump mammies, happy to serve; like her husband, she viewed the representation of refined African American types on the stage as important political work. A talented dancer, Aida improvised original routines that her husband eagerly introduced in the shows; when In Dahomey was moved to England, Aida proved to be one of the strongest attractions. Society women invited her to their homes for private lessons in the exotic cakewalk that the Walkers had included in the show. After two seasons in England, the company returned to the United States in 1904, and it was Aida who was featured in a New York Herald interview about their tour. At times Walker asked his wife to interpret dances made famous by other performers—one example being the "Salome" dance that took Broadway by storm in the early 1900s—which she did with uneven success.

After a decade of nearly continuous success with the Williams and Walker Company, Aida's career took an unexpected turn when her husband collapsed on tour with Bandanna Land. Initially Walker returned to his boyhood home of Lawrence, Kansas, where his mother took care of him. In his absence, Aida took over many of his songs and dances to keep the company together. In early 1909, however, Bandanna Land was forced to close, and Aida temporarily retired from stage work to care for her husband, now clearly seriously ill. No doubt recognizing that he likely would not recover and that she alone could support the family, she returned to the stage in Bob Cole and J. Rosamond Johnson's Red Moon in autumn 1909, and she joined the Smart Set Company in 1910. Aida also began touring the vaudeville circuit as a solo act. Less than two weeks after Walker's death in January 1911, Aida signed a two-year contract to appear as a co-star with S. H. Dudley in another all-black traveling show.

Although still a relatively young woman in the early 1910s, Aida began to develop medical problems that limited her capacity for constant touring and stage performance. As early as 1908, she had begun organizing benefits to aid such institutions as the Industrial Home for Colored Working Girls, and after her contract with S. H. Dudley expired, she devoted more of her energy to such projects, which allowed her to remain in New York. She also took an interest in developing the talents of younger women in the profession, hoping to pass along her vision of black performance as refined and elegant. She produced shows for two such female groups in 1913 and 1914—the Porto Rico Girls and the Happy Girls. She encouraged them to work up original dance numbers and insisted that they don stylish costumes on stage.

When Aida Overton Walker died suddenly of kidney failure on October 11, 1914, the African American entertainment community in New York went into deep mourning. The New York Age featured a lengthy obituary on its front page, and hundreds of shocked entertainers descended on her residence to confirm a story they hoped was untrue. Walker left behind a legacy of polished performance and model professionalism. Her demand for respect and her generosity made her a beloved figure in African American theater circles.

Sources: Jazz: Black Musical Theater in New York, 1890-1915. Washington, D.C., Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989, Thomas L Riis; Apeda Studio, NY.

George Walker

| |

|

One half of the famous vaudeville team Williams and Walker.

"We want our folks the Negroes, to like us. Over and above the money and the prestige is a love for the race. We feel that in a degree we represent the race and every hair's breadth of achievement we make is to its credit." (1909)

“There is no reason why we should be forced to do these old-time nigger acts. It’s all rot, this slap--stick--bandanna handkerchief--bladder in the face act, with which Negro acting is associated. It ought to die out, and we are trying hard to kill it.” Walker said that over 110 years ago.

George Nash Walker was born in 1873 in Lawrence, Kansas. He left at a young age to follow his dream of becoming a stage performer and toured with a traveling group of minstrels. After performing at shows and fairs across the country, Walker met Bert Williams in 1893 and they formed the duo known as Williams and Walker. During this time, white men performing in minstrel shows blackened their faces to pose as black performers. As a counter, Williams and Walker billed themselves as “Two Real Coons,” a descriptor that marked the two as black men and a reference to the derogatory term “coon” used to describe people of African descent in the United States. While performing as a vaudeville act throughout the United States, George Walker and his partner Bert Williams popularized the cakewalk, an African American dance form named for the prize that would be earned by the winners of a dance contest.

There was a distinct difference in presentation styles between the two performers. While the light skinned Bert Williams donned blackface makeup, George Walker was known as a “dandy” who performed without makeup. While Williams played the role of the comic figure, George Walker played the straight man, a dignified counterpoint to the prevailing negative stereotypes of the time. Offstage, Walker was an astute businessman who managed the affairs of the Williams and Walker Company, a venture that brought them fame and wealth nationally and internationally. In 1903, they performed In Dahomey at Buckingham Palace in London and then toured the British Isles.

Working in collaboration with Will Marion Cook as playwright, Jesse Shipp as director, and Paul Laurence Dunbar as lyricist, Williams and Walker produced a musical called In Dahomey in 1902. In this play, with its original music, props, and elaborate scenery, Walker played a hustler disguised as a prince from Dahomey who was dispatched by a group of dishonest investors to convince blacks to join a colony. A landmark production, In Dahomey was the first all black show to open on Broadway. Another musical, In Abyssinia opened in 1906 in New York at the Majestic Theater. Both of these productions used African themes and imagery, making them unique for the time. Other Williams and Walker productions include: The Sons of Ham (1900), The Policy Players (1899), and Bandana Land (1908).

George Walker married Ada (Aida) Overton, a dancer, choreographer, and comedienne in 1899. Ada (Aida) Overton Walker was known as one of the first professional African American choreographers. After falling ill during the tour of Bandana Land in 1909, George Walker returned to Lawrence, Kansas, the city of his birth where he died on January 8, 1911. He was 38.

Sources: Louis Chude-Sokei, The Last “Darky”: Bert Williams, Black-On-Black Minstrelsy, and the African Diaspora (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006); Kansas Historical Society

Jump to top

RSS feed- Latest items - Subscribe to the latest items added to this album

- ipernity © 2007-2024

- Help & Contact

|

Club news

|

About ipernity

|

History |

ipernity Club & Prices |

Guide of good conduct

Donate | Group guidelines | Privacy policy | Terms of use | Statutes | In memoria -

Facebook

Twitter